Transit - the New Urban Commons?

Cities compete for the 'echo boom' generation that isn't in love with cars and suburbs anymore, by wooing them with bike lanes, walk scores and robust transit. So if one reads on Trip Advisor that "Baltimore isn't a city known for its efficient public transportation system" (Trip Advisor), alarms should go off for anybody who cares about this city's future.

Many buses but often poor service: MTA buses stuck in traffic in Baltimore (Photo: ArchPlan Inc.)

The equity alarm should be especially shrill with the concentration of poverty in inner city neighborhoods so much in the news lately. Talk about equity quickly leads to transit as we shall see. Access and mobility are key for mitigating the inequities that arise from the sharp income disparities routinely found in the major US cities.

Transportation is the critical factor to get out of poverty (Seema Iyer, Associate Director, Jacob France Institute which runs the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance).

Transit as the new urban commons? (Photo: ArchPlan Inc.)

So, does Baltimore's transit system mitigate or exacerbate inequality? Is it as bad as Trip Advisor makes it?

High commute times are key indicators of communities in stress (over 45 minutes).

Opportunity mapping: the opportunities are highest where transit is low.

Transit does a better job providing high-skill residents access to high-skill jobs than it does mid-skill residents to mid-skill jobs and low-skill residents to low-skill jobs. (Brookings paper)

- improved transit;

- relocated people; or

- relocated jobs.

Improved Transit

So even if transit in a disinvested community starts near many front doors, transfers are required with increasingly sparser transit service the further out one gets. Plus even frequent bus transit traversing dense inner city communities suffers from being crowded, unreliable and slow while commuter lines from outer suburbs to the financial centers of downtown tends to be served by efficient express and commuter bus lines that hardly stop once they reach central neighborhoods.

While there are good operational reasons for that practice, it smacks of a prejudice against poorer communities. Attempts to have a version of express buses in poorer communities as well have been strated in Baltimore under the name Quickbus, essentially a bus that stops less often and duplicates a local service in the same corridor. Washington DC, Los Angelos and others have perfected such two tier bus services (Local/express) with good success. In short: Bus transit does not have to be inefficient or discriminatory. There are plenty of desirable and doable improvements for bus transit that could improve the heavily used routes through disenfranchised communities in Baltimore.

The minuscule role of transit on the US national scale.

Moving to Opportunity

Once even a federal program under the same name, it has lately languished and never reached its full potential. It is critically eyed by those who would be incentivized to move and those who live in opportunity areas as well. Dispersal of poverty by moving poor people has lots of problems, one is transit. To not force relocated people to waste a lot of their scarce resources on transportation, opportunity areas would still need excellent transit.

While better transit in outlying areas would create a more diverse ridership, there are limits to how far out transit can reach. A recent study shows, that many newer cities are built like suburbs, not to mention the actual suburbs outside of cities. Much post war development cannot be served effectively by the current modes of transit.

Baltimore's transit commute share is respectable.

Job relocation

The reverse would be to bring low skill jobs to where the people are, i.e. a reversal of the postwar trends. Low skill distribution or service jobs inside the core cities along with some type of renaissance of manufacturing may not be as far-fetched as it sounds.

Especially the so-called "legacy cities" have plenty of surplus land. Distribution centers where the people are instead of at dispersed locations could be a prerequisite once we talk same-day delivery. Urban manufacturing may one day flourish again thanks to 3-D printing, who knows?

The current state of affairs with cities surrounded by miles of flung-out low intensity junkscapes certainly is not sustainable for many reasons.

One of the effects of this type land use is that it leaves the poor hiking along arteries without sidewalks or decent transit, effectively disconnected from a large potential workforce. I would submit that the next city has to solve this problem not only in the interest of job access equity and shorter commutes but for a host of other reasons as well, both environmental and economical.

Which of these options cities would decide to go, trying to reduce disparities, trying to find common ground to heal the wounds of decades of discrimination, segregation and acrimony cities must look to transit as a potential unifier.

The more successful a city, the more diverse and integrated its transit ridership. Successful cities have better transit and a broader constituency across all races and income levels reaching from unions to employers and from students to seniors.

By contrast, cities with poor transit are places where transit in general, and the bus in particular, are treated as a mobility option of last resort which is used only by the poor and to be avoided by everyone else.

Since "everyone else" doesn't always have a car as a practical mobility option either, cities with poor public transportation routinely boast a whole fleet of apartment, hotel, student and employer shuttles representing a redundant, inefficient and costly solution.

These para transit-services are often a form of poorly disguised racism, they clog the streets and deprive public transit of riders needed to flourish. It is hard to see what is cause and what is effect in this "wicked problem."

Still, the desired outcome should be clear as glass: An efficient, reliable and convenient public transit system for all.

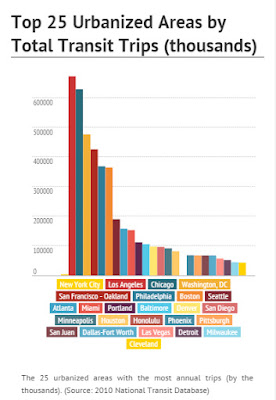

Baltimore's position in overall transit trips is #13 in this chart of US cities.

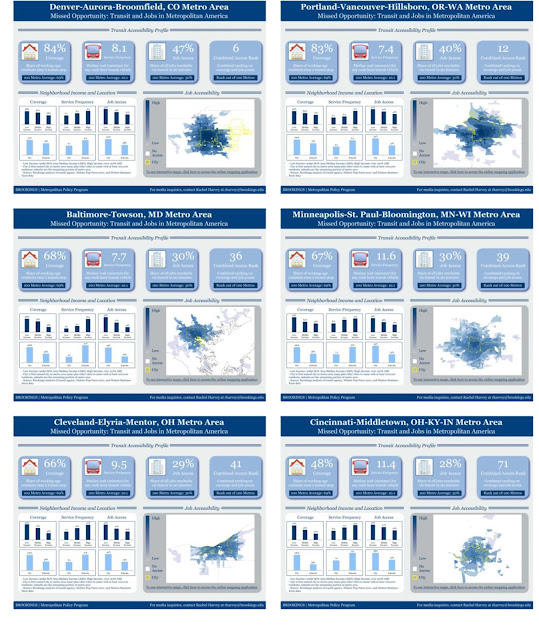

How important good transit really is for the well being of cities is regularly emphasized by business leaders, downtown boosters and community activists alike. Many studies show that transit, indeed, is a key element in addressing what ails many big US cities, including Baltimore. (For example see this see this 2011 Brookings report titled "Missed Opportunity".

Transit is not only needed to please millenials or to provide equity to those who live in poverty but is is also necessary to keep the dense job centers dotting a very small area of many states viable. In Maryland these concentrations cover only 1.2% of the land area but hold 43% of all jobs. (Jason Sartori, "transportation, Opportunity and Equity", 2013).

Baltimore's downtown is not only one of those job centers, it is the biggest one! The idea that one could warehouse the poor in a large city like Baltimore, lock them up and lose the key is not only morally repulsive, it is also economically perilous. Core cities have historically played and continue to play a big role in the health of metro regions.

Consequently, "opportunity mapping" proves that opportunity cuts both ways.

Initially defined as the metrics that characterize an area in regards to opportunities an individual has for a quality life with access to education, jobs, retail and entertainment, opportunity can also be defined as the metrics that are needed for economic centers or job hubs to flourish.

Clearly, good access for the workforce is one of those metrics and as important as the easy in and out of goods.

To approach the goal of better transit in a realistic way, it helps to understand better how a particular system or geographic area ranks under the various metrics used by the transit industry, planners and urban analysts.

In the following I assembled a few results of such comparisons for Baltimore. Depending on what gets measured and who the competition is, the following studies and charts show, that Baltimore's transit is far from being one of the worst in the country. in some, the Baltimore metro area actually scores pretty well:

On time performance in MTA's annual reporting 83% for buses but with a margin of 3 minutes early and 5 minutes late.

Job access

The University of Minnesota ranked large American cities according to jobs access measured as the number of jobs that can be reached by transit within 30 minutes (2014).

Baltimore ranked #14, behind Minneapolis and Denver and the usual suspects (New York, Boston, Philly etc.) but ahead of Miami, Phoenix, Houston and San Diego. A 2011 Brookings investigation about job access placed Baltimore ahead of Cleveland, Cincinnati and Minneapolis but far behind Denver, Co and Portland, OR with the aggressive light rail plans!

Mode share

For mode share of transit, the Victoria Transport Policy Institute determined that for 2001 Baltimore was among the top seven US cities and ranked right behind Philadelphia and before Pittsburgh and Seattle.

However, ten years later Baltimore had slipped because the rail systems of these cities had exceeded Baltimore. However according to a 2010 National Transit Database it was still #13 in the nation in terms of annual transit trips.

Agency evaluation

The Florida based National Center for Transit Research evaluated transit agencies against its peers in comparable groups (by geography and size) and used a lot metrics such as Service Supply/Availability, Service Consumption, Quality of Service, Cost Efficiency, Operating Ratios and vehicle Utilization.

In its evaluation points were given for deviation from the mean within the peer group. MTA comes in dead last in the eight large agencies in the Northeast but not all that much worse than WMATA in DC. The study uses 2004 data.

Light Rail

A 2011 Transportation Research Board looked at light rail transit (LRT) in eight U. S. metropolitan areas—Phoenix, Arizona; Sacramento and San Diego, California; Denver, Colorado; Saint Louis, Missouri; Portland, Oregon; Dallas, Texas; and Salt Lake City, Utah—which all carried 20% or more of the metropolitan area's total fixed-route ridership. Baltimore was not one of them (TRB study).

Metro Rail

In terms of heavy rail (Metro) Baltimore ranks # 11 of 15 systems in the country, behind Miami Dade's Metrorail and ahead of the Tren Urbano of San Juan.

MTA's commuter trains (MARC)

Transit Score

Maybe the "Transit Score" index compiled by the folks that came up with the popular "Walkscore" gives the best useful indicator for the quality of a transit system since it isn't put together by a transit agency and applies the user and not the provider perspective.

The 2013 results give Baltimore 57 points, with 80 being the highest and 23 the lowest. This puts Baltimore within the top 10 cities in the US, well ahead of its ranking based on size (#16):

- New York (81)

- San Francisco (80)

- Boston (74)

- Washington, D.C(69)

- Philadelphia (68)

- Chicago (65)

- Seattle (59)

- Miami (57)

- Baltimore (57)

- Portland (50)

- Los Angeles (49)

- Milwaukee (49)

- Denver (47)

- Cleveland (45)

- San Jose (40)

- San Diego (36)

- Austin (33)

- Sacramento (32)

- Columbus (29)

- Raleigh (23)

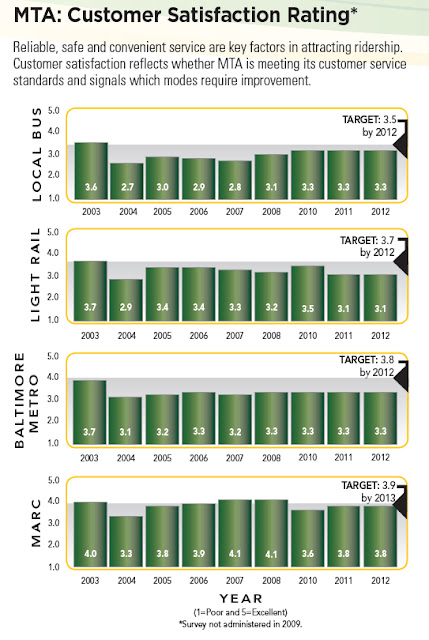

How MTA ranks their customer satisfaction.

Conclusion

The prevailing negative perceptions of Baltimore's transit may not accurately describe its actual role or performance. In that the MTA is certainly not unique but shares the fate of a poor reputation with many of its peer systems across the country.

What this region has to watch out for is that the pervasive perception results into slippage while peers move forward. The sentiment of users, particularly those who depend on the system daily, cannot be underestimated.

What the powers to be do with them will determine how Baltimore and other metro regions like it will fare in the future.

Will it be a city that can attract upwardly mobile new residents and a city that provides mobility for its poor? Or will it be a city whose transit system makes the income divide worse, lets people be stuck in hopelessness and has given up on keeping up with its peers when it comes to investing in and expanding transit?

It stands to reason that the decision about the Red Line currently in the hands of the new Maryland Governor will tip the scale into the one or the other direction.

2011 Brookings Transit and Jobs in Metropolitan America Study:

Brookings Scores of Baltimore and some peer cities. Baltimore's 68% of households with transit access compares favourably to Minneapolis (67%), Cleveland (66%) and Cincinnati (48%) but is worse than Portland's 83% and Denver's 84%.

The Transit Score is dependent on the "usefulness" of routes in a city, which is quantified by a combination of the proximity of a point to the nearest stop on a route, the frequency of the route and the type of route.

A raw Transit Score is calculated block by block by summing the value of all nearby routes, which are then weighted - with rail services deemed preferable to ferries and cable car/trams, which are preferable again to bus routes. Blocks are also weighted by population density so that areas with more people living in them have a larger effect on the score. This data is normalized to make a comparable score of between zero and 100, calibrated against a notional "perfect score" location based on the average of five city centers where full transit data was available.

Related Articles

- Ten Ways to Improve Bus Transit Use and Experience

- 3 Ways the "Internet of Moving Things" is Transforming Bus Travel

- Can Big Data Deliver Evidence Based Urban Design?

- The Top 10 Benefits of Public Transportation

- Greening Bus Fleets Requires a Range of Strategies

- What Cities Can Learn From Greater Toronto's Transit-Oriented Development

- How Mapping Public Transport Can Help Commuters